What is Relevance?

The first challenge in building the pipeline was to define what qualifies as a relevant press release. The aim was to translate the implicit knowledge within the newsroom about which research projects may matter to the public into an explicit prompt that an LLM can apply consistently. However, before attempting this, we needed to understand whether humans themselves agree on what relevance means. If there is no stable consensus among people, no model – regardless of prompting strategy – can reproduce it reliably.

To test this, we created a small subset of idw press releases and had three human annotators from the editorial staff and our lab rate each text as either relevant (1) or not relevant (0). We then calculated Krippendorff’s Alpha, a widely used metric for inter-rater-agreement, to quantify the level of consensus.

The resulting value was 0.404, which falls between a “fair” and “moderate” agreement range. This indicates that even among trained human readers, identifying relevance is not a straightforward task. For the project, this means that the challenge is not only technical. The annotation process itself requires clear and operational guidelines so that human annotators apply the same criteria consistently before these criteria can be translated into a prompt for the model.

To address this issue, we first examined the press releases with the highest levels of disagreement. These cases turned out to be predominantly edge cases, such as graduate programmes, institutional initiatives, or projects involving researchers outside Germany. By reviewing these examples in detail, we were able to create guidelines that define relevance in the context of research projects.

Next, we repeated the process: a new subset of press releases was annotated by the same group of human annotators, this time applying the clarified guidelines that had been developed from the earlier analysis. This time, Krippendorff’s Alpha increased to 0.635, indicating a “substantial” level of agreement. With a more consistent human baseline established, we were ready to move on to the next step: creating the classifier module.

The Classifier Module

With clearer relevance guidelines in place, the next step was to formulate a system prompt that operationalises these rules for the LLM. The prompt encodes the criteria for identifying research projects and the exclusion rules. It also enforces strict binary output to ensure consistent classification.

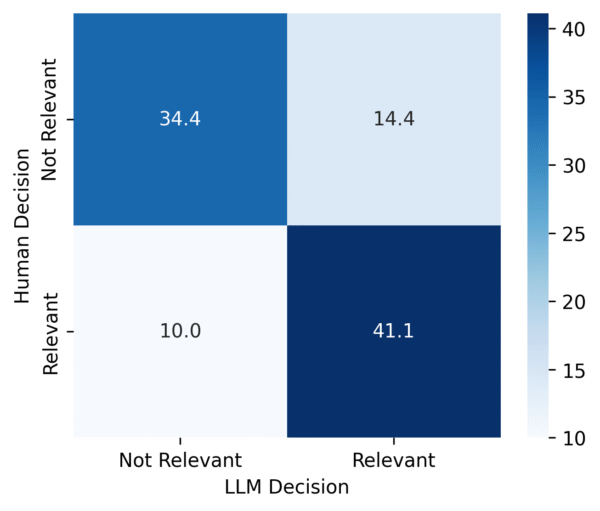

To evaluate the prompt, we created a new subset of idw press releases. This time, the four human annotators each rated a different portion of the subset, while the LLM classified the entire set. The goal was to assess how closely the model’s decisions matched the human-labelled data.

To measure this, we used precision and recall as evaluation metrics. Precision measures how many of the items the model marked as relevant were actually relevant (i.e., judged as relevant by human annotators). Recall measures how many of the truly relevant items the LLM successfully identified. In simple words, precision captures correctness, while recall captures completeness.

For our test set, the classifier achieved:

- Precision: 0.740

- Recall: 0.822

The confusion matrix illustrates the underlying distribution of true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives.

These values are not perfect, but sufficient for us to use the classifier in our production context. Notably, there are a few ways to further improve performance beyond prompt adjustments. One possibility is fine-tuning an LLM.

Excursus: When Fine-Tuning Becomes Useful

Foundation models are pre-trained on broad and diverse training data and can handle many tasks out of the box. Fine-tuning adapts such a model to a narrower domain by training it further on examples that reflect the specific task. In the context of classification, fine-tuning allows a model to learn patterns that may not be captured through prompting alone, especially when the classification depends on subtle cues.

For our project, we used OpenAI models. OpenAI offers a fine-tuning interface for selected models, which makes it straightforward to train a custom variant if you are already working within their ecosystem. The main requirement is a set of paired training examples. We simply used the human-annotated data generated during the validation process as the basis for this training set. After preparing the dataset in the correct format, fine-tuning can be initiated directly through the dashboard or API.

If you use local or open-source models instead, tools such as Unsloth provide an easy entry point into fine-tuning. These methods can be applied to smaller models running on local hardware and allow more control over training and fine-tuning methods.

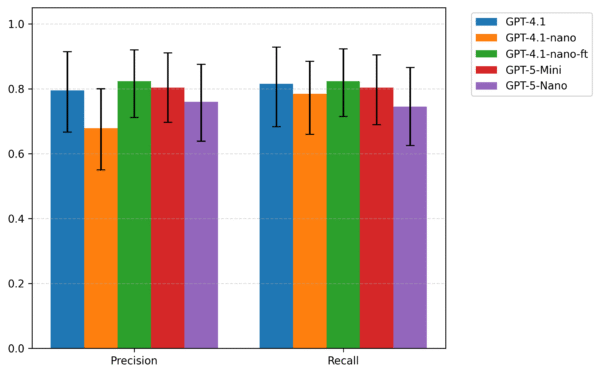

To explore whether fine-tuning our classifier would improve performance, we fine-tuned the GPT-4.1-nano model using the human-annotated relevance data that we had collected during the validation process. The dataset was split into a training set for fine-tuning the model and a test set for evaluating the results.

As shown in Fig. 2, the fine-tuned GPT-4.1-nano model achieves higher precision and slightly higher recall within the evaluation sample. However, the confidence intervals around these estimates are wide and overlapping, meaning the observed differences cannot be interpreted as evidence of a generalizable improvement in performance. These results indicate that fine-tuning may influence performance, but the available data are too limited to draw firm conclusions about its true effect.

Given this uncertainty, we ultimately decided not to adopt the fine-tuned model in the production pipeline. Relative to the GPT-5-mini baseline currently in use, the fine-tuned GPT-4.1-nano does not demonstrate a reliably superior performance, and the small training set further limits the robustness of the findings. In addition, OpenAI no longer supports fine-tuning for the newest model series, introducing a long-term maintenance risk. For these reasons, we opted to retain the existing GPT-5-mini baseline while keeping fine-tuning as a direction for future exploration as more data become available.

Depending on the LLM you use, the size of your available training dataset, and the performance requirements of the classifier, fine-tuning can nevertheless be a viable and effective method for improving results.

With this step completed, we now have a classifier that can reliably determine whether an idw press release contains a relevant research project or not. The next stage was to build the extractor module.

The Extractor Module

The second component of the pipeline is the extractor module. Its task is to identify and extract key information from each press release. To do this, we prompted a second LLM to extract and return a predefined set of fields (such as project title, start and end dates, funding amount, partners, and project aims) in a structured format.

Testing the extractor required a different approach than testing the classifier. The output is not a binary label that can be compared directly to a human judgement. Instead, it consists of multiple fields that contain dates, names, numerical values, and short textual descriptions. In principle, this could be evaluated against a gold standard dataset produced by humans. However, creating such a dataset is time-consuming and was outside the scope of this initial development phase.

Instead, we used a more pragmatic evaluation method. The same three human annotators reviewed the extracted outputs and provided targeted feedback through a free-text field (e.g., ‘project aims are too general,’ ‘date formats are inconsistent,’ or ‘funding information is incorrect.’). We then grouped and classified this feedback using an LLM to identify recurring patterns and derive error types across traces. This error-analysis step allowed us to revise and refine the extraction prompt iteratively.

After a few rounds of adjustment, the annotators agreed that the extractor module performed reliably and produced structured data of sufficient quality for editorial use. With this step, the LLM components of the pipeline were complete. Together, the classifier and extractor form the core logic of our pipeline: first identifying relevant press releases, then extracting their content.

The final post will present the complete pipeline and outline the benefits and limitations of this approach in newsroom practice.